"It is not too much to say that ritual is more to society than words are to thought. For it is very possible to know something and then find words for it. But it is impossible to have social relations without symbolic acts." (Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger, p. 62)

The sociologist Paul Lukes suggests that we use ritual to refer to "rule-governed activity of a symbolic character which draws the attention of its participants to objects of thought and feeling which they hold to be of a special significance."

In How Societies Remember, Paul Connerton calls for the analysis of "social habit-memory" as consisting essentially of legitimating performances, a particular kind of ritual. He draws upon the work of Maurice Halbwachs, (Les cadres sociaux de la m moire and La m moire collective ) who thought of memories as bound together into an ensemble of thoughts common to a group. For Halbwachs, groups provide individuals with frameworks within which there memories are localized, by a kind of mapping into both the mental and material spaces of the group. For Halbwachs the idea of an individual memory, absolutely separate from social memory, is an abstraction almost devoid of meaning.

All rites are repetitive, and repetition automatically implies continuity with the past. Drawing on Claude Levi-Strauss, Giorgio Agamben describes the function of ritual to adjust the contradiction between mythic past and present, reabsorbing all events into a synchronic structure, while the function of play is a symmetrically opposed operation: to break down the whole structure into events.

Mary Douglas criticizes modern anthropology for thinking of magic as efficacious rite. For her, this is a European belief that institutes a false distinction between primitive and modern.

In modern religous life, there is a long and vigorous anti-ritualistic tradition, echoing the parable of the Pharisee and the Publican, that claims that external forms can become empty and mock the truths they stand for. (in this sense, they can be described as mechanical.) But this account, which contrasts the formalisms and "emptiness" of ritual with acts that are "sincere" or "authentic," ignores the function of ritual as the expression of feeling or belief. Instead, rites have the capacity to give value and meaning to the life of those who perform them. (Connerton, pp 44-5) In How Societies Remember, Paul Connerton stresses the importance of commemorative rituals. The feature that they share, and which sets them apart from the more general category of rites, is that they do not simply imply continuity with the past but explicitly claim such continuity. Connerton infers that commemorative ceremonies play a significant role in the shaping of communal memory.

Do rituals create the beliefs that they are meant to express? see ideology.

One consequence of the failure of ritual is panic.

Gregory Bateson describes ritual in terms of unusually real or literal ascriptions of logical type

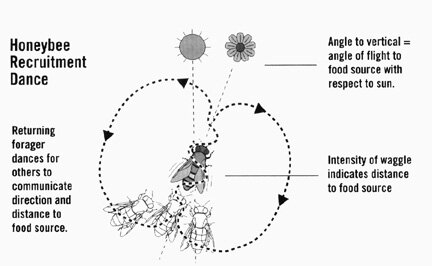

In biological accounts of communication, ritualization is "the evolutionary modification of a behavior pattern that turns it into a signal (sign) used in communication or at least improves its its efficacy a a signal (sign)." (Wilson, Sociobiology, p.594) According to contemporary neo-Darwinism, adaptive pressures will select certain behaviours as important references. For instance, in flocking birds, it is important to know when to take off. In a speculative account of the origins of language, Robert N. Brandon describes a process of ritualization which selects behaviour patterns with perceived iconicity to the referent of the sign, for example, when birds just prior to flight characteristically crouch, raise their tails, and slightly spread their wings. According to Brandon, these iconic signs can subsequentlybe transferred to other referents, as in mating behavior, for instance. While they become increasing symbolic (arbitrary) in synchronic analysis, they remain "phylogenetically iconic." (?)

The effectiveness of such a sign can be increased through increased ritualization, for example, in pigeons, where the preflight pattern of behaviour which serves as sign of flight has been exaggerated beyond what is physiologically necessary. Konrad Lorenz studied these movements in the 1930's and called them "intention movements." For Lorentz and Tinbergen, intention movements provided the raw material from which signals are sharpened through natural selection. The term was subsequently dropped by ethologists, presumably by behaviorists who rejected the mentalistic implications of the term. For Ronald Griffin, in Animal Minds, "we may hope that the revival of interest in animal thinking will lead cognitive ethologists to reopen the study of the degree to which intention movements may indeed be signals of conscious intent." (p. 16)

see local / global for the role of ritual in maintaining locality. For Arjun Appadurai, One of the most remarkable features of the ritual process is its highly specific way of localizing duration and extension, of giving these categories names and properties, values and meanings, symptoms and legibility.