In 1892, Charles Darwin categorized human affects into seven or eight discrete expressions, each with its own facial display: happiness, sadness, fear, anger, disgust, surprise, interest, perhaps shame, and their combination. (The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals) According to Darwin, "The same state of mind is expressed throughout the world with remarkable uniformity." He postulated that these innate patterns of feeling and facial display evolved as social signals "understood" by all members to enhance species survival. (cf ritualization ) For Darwin, our expressions of emotion are universal (that is, innate not learned) and they are products of our evolution. They are also, at least to some extent, involuntary, and feigned emotions are rarely fully convincing.

psychological

agency

anosognosia

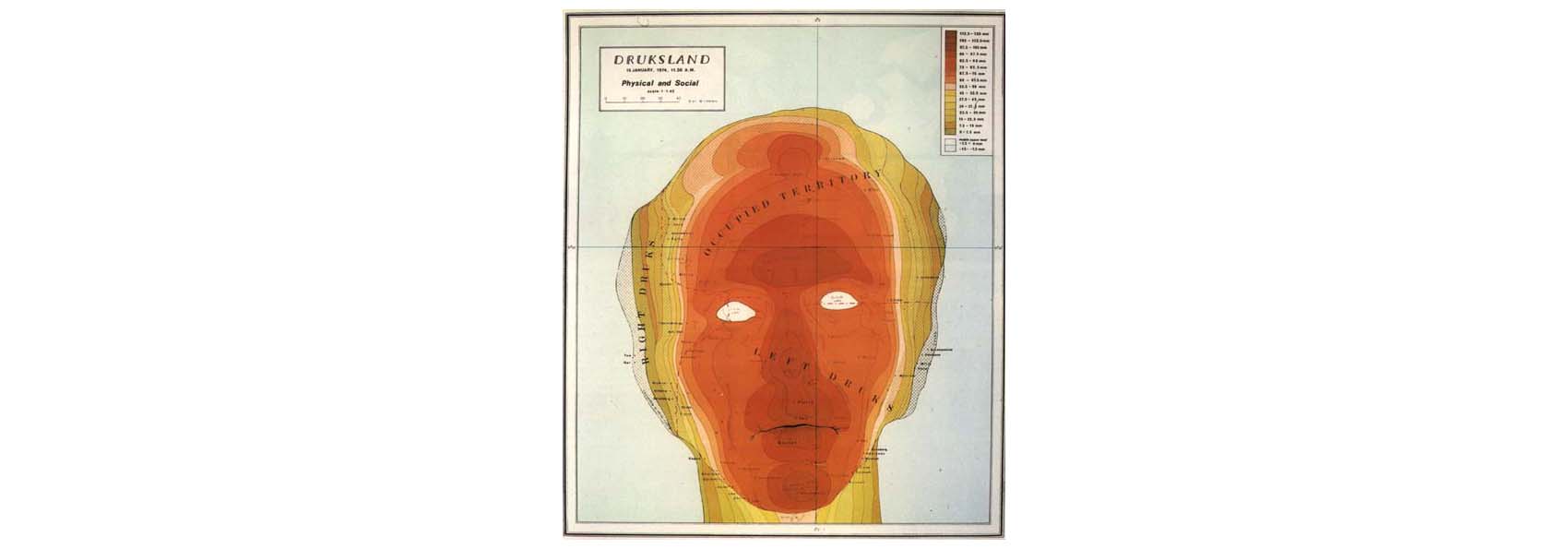

The tendency to ignore or sometimes even to deny that one's left arm or leg is paralyzed was termed anosognosia, ("unaware of illness") by the French neurologist Francois Babinski, who first observed it clinically in 1908. In anosognosia, the patient is unaware of or denies a paralyzed limb, and in hemianosognosia, the patient behaves as if half the body were nonexistent. The "counterfeit" limb is a milder version of anosognosia, where the limb seems less than real. Oliver Sachs describes how his paralyzed leg had "vanished, taking its place with it...The leg had vanished taking its 'past' away with it. I could no longer remember having a leg." (See Oliver Sachs, A Leg to Stand On, New York, 1984,)

Read Moreanxiety

For Kurt Goldstein, anxiety has no "object," and is qualitatively different from fear. In fact, for Goldstein, fear is the anticipation of anxiety. For Kierkegaard and Heidegger, anxiety deals with "nothingness." It is a breakdown of both world and self. For Goldstein, the drive to overcome anxiety by the conquest of a piece of the world is expressed in the tendency towards order, norms, continuity, and homogeneity. Deleuze and Guattari echo this diagnosis when they claim that striation is negatively motivated by anxiety in the face of all that passes, flows, or varies and erects the constancy and eternity of an in-itelf.

Read Moreattention

Attention, according to William James, is "the taking possession by the mind, in clear and vivid form, of one out of what may seem several simultaneously possible objects or trains of thought." Any model of attention must account for its selectivity, for the fact that, after an animal learns a skill, it becomes automatic (or unconscious), for the ability to interrupt automatic acts by attention to novelty, and for the ability to direct attention specifically by conscious means. (Edelman)

Read Morebody

Aristotle distinguished between the body and the soul. The latter referred not only to the principle of life, but to the form of a particular living body. Thus the soul is the organization of the body. (cf. organism) Aristotle rejected the doctrine of the Pythogoreans, according to which the soul can clothe itself in different bodies. (see clothing/garment ) Instead, a particular soul is the entelechy, or formative force of a particular body, and the individuality of a particular man. Thus every particular soul requires a connection to a particular organic whole. At the same time, he upheld a division between matter and form which describes, for example, the relation between the eye and sight. When the power of sight is absent, the eye is no longer an eye in the proper sense. After taking the position that "..there seems to be no case in which the soul can act or be acted on without involving the body," Aristotle goes on to suggest that thinking is the one specific activity of the human soul which is capable of separate and independent existence from any connection to the body. (see also subject )

death

In Totem and Taboo, Freud traced the evolution of attitudes toward death in human civilization -- toward individual death and death in general -- to death as the ultimate expression of human helplessness. (Shur, Freud Living and Dying, p. 280)

Read Moredesire

Freud's use of the word Wunsch, which corresponds to 'wish' does not have the same connotations as the English word 'desire" or the French désir . His clearest elucidation of the concept is in the theory of dreams. Freud does not identify need with desire. Need can be satisfied through the action which procures the adequate object. (eg. food) Wishes, on the other hand, are governed by a relationship with signs, with memory-traces of excitation, and the desire to re-cathect mnemic images. The Freudian conception of desire refers above all to unconscious wishes, bound to indestructible infantile signs, organized as phantasy.

Read Moreego

what is the relation between the ego and the subject? According to Freud, the ego is an agency of the psyche,by means of which the subject aquires a sense of unity and identity, "a coherent organization of mental processes." (XIX,17.) Through consciousness , the ego is the site of differentiation between inside and outside, between "subjective" and "objective." The passage from the ego as biological individual to the ego as an agency: "such is the entire problematic of the derivation of the psychoanalytic ego . " (Jean Laplanche, Life and Death in Psychoanalysis, p. 76)

Read Moreembodiment

Embodiment is the line between psychology and biology. One important feature of embodiment is that the interaction between the body and cognition is circular. Thus posture, facial expressions, or breathing rhythm are in a feedback loop with motor movement, mood, and cognition. I am bouncing along the street because I am happy but I am also happy because I am walking with a spring in my step.

Read Moreempathy

In the late nineteenth century, the concept of Einfühlung , as "feeling into," was proposed by Rudolph Lotz and Wilhelm Wundt. E. G. Tichener, a student of Wundt, coined the English translation "empathy" in 1910, using the Greek root pathos for feeling and the prefix em for in. Empathy was developed as an aesthetic theory in the work of Theodore Lipps and others.

Read Morefetish

The three primary models of fetishism -- anthropological, Marxian, Freudian--all define the fetish as an object endowed with a special force or independent life. Marx called this transference, Freud called it overvaluation. In this sense the fetish is not a representation. It does not refer to something outside itself.

Deleuze and Guattari criticize psychology for not seeing the " becoming-animal, that is affect in itself, the drive in person, and represents nothing." They describe children as continually undergoing becomings of this kind, and find these "unnatural participations" in fetishism and particularly masochism. (1000 Plateaux, p. 259)

The power of the fetish can also be seen in the confusion of animate and inanimate of the Golem or cyborg.

forgetting

Are all memoriespermanently stored somewhere in the mind, so that details we cannot remember at a particular time could eventually be recovered with the right technique? Or are some experiences permanently lost from memory?

Read Moreheimlich / unheimlich

"With Freud indeed, foreignness, an uncanny one, creeps into the tranquility of reason itself...Henceforth, we know that we are foreigners to ourselves, and it is with the help of that sole support that we can attempt to live with others." (Julia Kristeva, Strangers to Ourselves, p. 170)

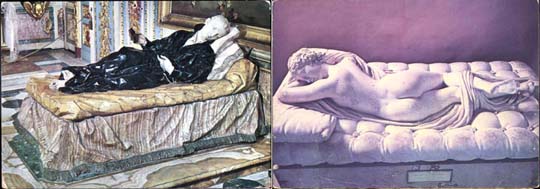

In an article published in 1906, the German psychiatrist Ernst Jentsch published "Zur Psychologie des Unheimlichen ", an essay on the uncanny as an affective excitement -- a sensation of unease, of disorientation, of not being quite "at home" -- which a "fortunate formation" of the German language conveys quite clearly, since Heim specifically refers to the home. Thus, for Jentsch the experience of the new, the foreign, and the unusual can provoke mistrust, unease, and even hostility, as opposed to the familiar forms of the traditional, the usual, the hereditary which are a source of comfort and reassurance. While the familiar may even appear self-evident, the unfamiliar can create uncertainty and disorientation, and threats to the everyday sense of intellectual mastery. While the intensity of feeling associated with this disorientation can vary considerably, the sense of the uncanny is most particularly aroused in conditions of "doubt as to whether an apparently living being really is animate and, conversely doubt as to whether a lifeless object may not in fact be animate." (The point is taken up by Freud in Das Unheimliche ) Fear, terror, and horror can result. The impression of the uncanny is often provoked by wax figures, automata, panopticons, and panoramas, and in recent years the "uncanny valley" has been proposed to explain the unease that lifelike robots can provoke -- almost but not quite animate.

Read Moreimaginary / symbolic

In the sense given to these terms by Jacques Lacan, the three essential orders of the psycho-analytic field are the Imaginary, the Symbolic, and the Real. The concept of the "imaginary" can be grasped through initially through Lacan's theme of the " mirror stage." Lacan proposed that the ego of the infant -- as a result of its biological prematurity -- is constituted on the basis of the image of the counterpart (specular ego). Following from this primordial experience, the Imaginary defines the basically narcissistic relations of the subject to his ego, the intersubjective relations of a counterpart -- an other who is me, a type of apprehension characterized by resemblance and homeomorphism -- a sort of coalescence of the signifier and signified. (from Laplanche and Pontalis) While Lacan's use of the term "Imaginary" is highly idiosyncratic, he insists that all imaginary behavior and relationships are fundamentally deceptive, and that the intersubjective realm of the symbolic must be separated out from the Imaginary in analytic treatment.

immersion

There are a number of ways to approach the metaphors of immersion and navigation that suffuse descriptions of technology. The psychological theme of the "oceanic" is explored by Freud in Civilization and its Discontents among other places, and provides an interpretation of the sense immensity that the term conveys.

instinct

Instinct, for both psychology and ethology is a preformed behavioral pattern, often manifesting itself immediately from birth. Its arrangement is determined hereditarily and is repeated according to modalities relatively adapted to a certain kind of object. (from Laplanche, Life and Death in Psychoanalysis) Instinctive behaviour contributes to the survival of species and is evolved like morphological structure. (Bowlby) Charles Darwin outlined the modern theory of instinct in The Origin of Species.

Read Moreintersubjectivity

Intersubjectivity is a "deliberately sought sharing of experiences about events and things."

The primary model of intersubjectivity is " affect attunement" in the mother-infant dyad and the "holding environment." (see psycho-sexual space )

love

For Plato, love is an intermediate state between possession and deprivation. For Alain Badiou, love is "the procedure that makes truth out of the disjunction of sexuated positions." (Infinite Thought, p. 163)

Freud stressed the risks of love as a means to happiness. "We are never so defenceless against suffering as when we love, never so helplessly unhappy as when we have lost our loved object or its love." (Civilization and its Discontents, p.29) For Freud, "There is good reasons why a child sucking at his mother's breast has become the prototype for every relation of love. The finding of an object is in fact a re-finding of it." ("Three Essays on Sexuality) Jean Laplanche points out that a displacement has taken place nonetheless. "The lost object is the object of self-preservation, and the object one seeks to refind in sexuality is an object displaced." (Life and Death in Psychoanalysis, p. 20)

narcissism

In Civilization and its Discontents, Freud describes primary narcissism as that primal state where id, ego and external world are not differentiated. As he develops the concept of primary narcissism, libido theory and ego theory become inseparable. In his essay "On Narcissism," of 1914, Freud describes the origin of the ego in terms of the subject's ability to take itself or part of its own body as a love object.

Read More