In The Critical Historians of Art, Michael Podro distinguishes questions that are "archaeological" from "critical" questions. The latter, which address the role and nature of concepts of art, "require us to see how the products of art sustain purposes and interests which are both irreducible to the conditions of their emergence as well as inextricable from them." (pxviii)

Read Moreconceptual

critique of Judgement

For Kant, The power of judgement is a mediating element between (theoretical) understanding and (practical) reason, between concepts of nature and concepts of freedom (natural philosophy and moral philosophy, the sensible and the supersensible), between the is and the ought.

Read Moredistinctions theory

Is hierarchy inevitable when making dichotomous distinctions? Does one term inevitably become the priveleged term and the other its suppressed, subordinated, negative counterpart?

Read MoreEpigenesis/Preformation

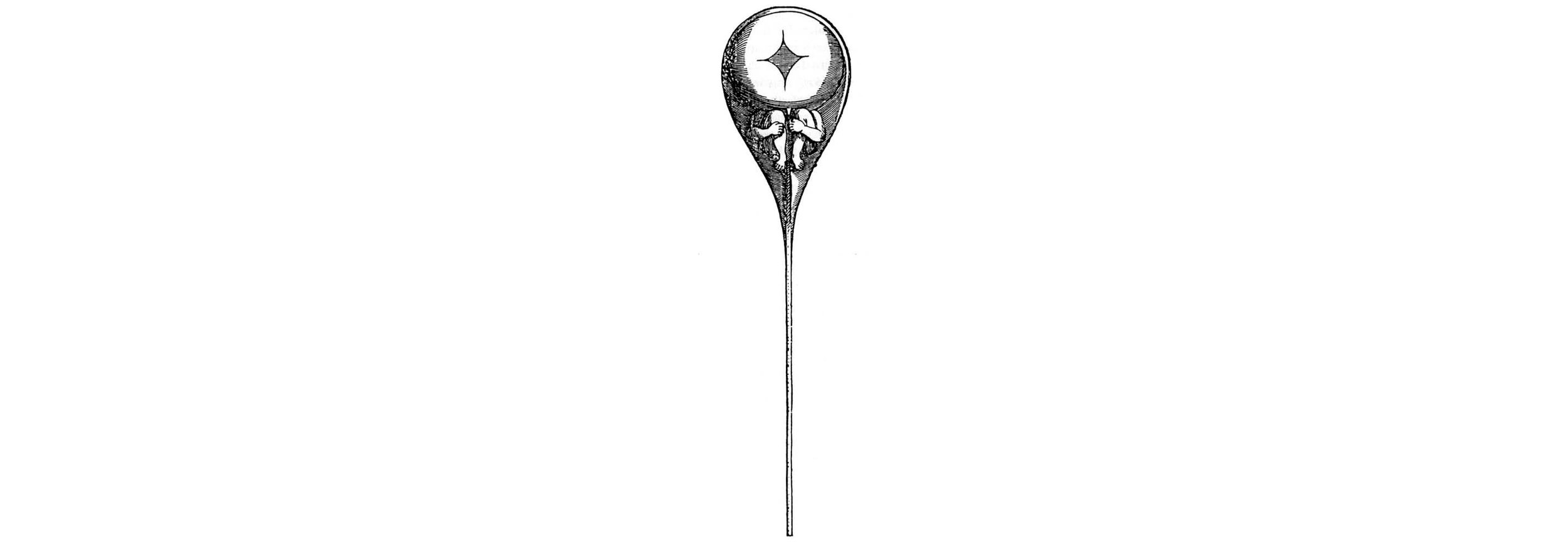

One of the most important issues in the premodern biology of the 18th century was the struggle between preformationist and epigenetic theories of development. The preformationist view was that the adult organism was contained, already formed in miniature, in the sperm, and that development was the growth and solidification of this miniature being. Preformationists assumed that the germs of all living beings were preformed and had been since the Creation. Preformationism sought to maintain and secure--against the irritation posed by the complexity of organic phenomena--the claim for a thorough and rational determination of the material world.

Read Moreevent

For Kant, the concept "cause" is intimately tied to that of "event", in such a way that, unless the former concept were applicable, there would be no concept of an event as an objective happening. At the heart of scientific theories are models or representations that describe a mechanism by which a cause, be it event or state or potent thing or substance, brings about the effect, event, or state. (Rom Harré)

Read Moreexperimental

"The word experimental is apt, providing it is understood not as descriptive of an act to be laterjudged in terms of success and failure, but simply as of an act the outcome of which is unknown." John Cage, Silence, p.13.

Would this characterization apply to scientific experiment?

field

jackson pollock number IIa, 1948

In The Evolution of Physics, Einstein described the collapse of the mechanical world-view, leaving an intellectual vacuum before the radically new "field" theory could emerge. A field describes the behaviour of a dynamic system that is extended in space, through kinetics (interaction in time) and relational order (in space). It is a function of space and time coordinates that assigns a value of the field for each of the coordinates. Jackson Pollock, Number IIA, 1948

In current physics, several kinds of fundamental fields are recognized: the gravitational and electro-magnetic fields and the matter fields of quantum physics. Physicists talk about two kinds of fields: classical fields and quantum fields, although, for the most part, they believe that all fields in nature are quantum fields, and that a classical field is just a large-scale manifestation of a quantum field.

"A classical field is a kind of tension or stress that can exist in empty space in the absence of matter. It reveals itself by producing forces, which act on material objects that happen to lie in the space the field occupies." (Freeman Dyson, "Field Theory," in From Eros to Gaia, p. 93)

frame

If distinctions are "frames" for observing and describing identities, we will need a theory of frames, including, as Derrida would say, a frame for the theory of frames. In the Parergon quote, Derrida twists the theory of the frame to directly connect its inside and outside. The lack of a theory of the frame is directly connected to the place of lack within the theory.

Read MoreGestalt

The word "Gestalt" is usually translated as form, although it might be better understoond as "organized structure," as opposed to "heap", aggregate, or simple summation (what Max Wertheimer called "and-sums.")

Read Morehermeneutics

Hermeneutically oriented philosophy aims at deciphering the meaning of Being, the meaning of Being-in-the-world, and its central concept if that of interpretation.

In it broadest sense hermeneutics means "interpretation", but in a more specialized sense, it usually refers to textual interpretation and to reading. Reflection on the practice of interpretation arose in modern European culture as the result of the attempt to understand what had been handed down within that culture from the past.

Interpretation (Auslegung ) is now seen as the explicit, conscious understanding of meanings under conditions where an understanding of those meanings can no longer be presumed to be a self-evident process but is viewed as intrinsically problematic; it is here assumed that misunderstandings about what we seek to interpret will arise not simply occasionally, but systematically. (Paul Connerton, How Societies Remember, p 95)

Read Morehomogeneity / heterogeneity

"The bodies of organisms are not homogeneous but heterogeneous, consisting of organs or parts which in substance or composition differ from each other. This heterogeneity in composition is of course an objective expression of the process of Differentiation. " (William Bateson, p. 18)(see embryo) "In the bodies of living things heterogeneity is is generally ordered and formal; It is cosmic, not chaotic." (p.19)

Read Moreidea

Socrates first discovered the concept, or eidos as the relation between the particular and the general and as a germ of a new meaning of the general question concerning being. This meaning emerged in its full purity when the Socratic eidos went on to unfold into the (transcendental) Platonic "Idea." (see also essence) The eidos is absolutely and eternally real, but in respect to each single realization, it is the possible, its potentiality.

Plato and Euclid developed an indissoluble partnership between geometrical and philosophical ideas of truth. The Platonic concept of the theory of ideas was possible only because Plato had continually in mind the static shapes discovered by Greek mathematics.(see form.) Euclid's geometry was based on figures that are radically removed from experience. Not only the idealizations of point, line, and plane, but the idea of similar triangles, whose differences are considered inconsequential or fortuitous, and that become identified as "the same," mark an immense step away form ordinary perception. On the other hand, Greek geometry did not achieve completion as a real system until it adopted Plato's manner of thinking, in which truth was understood as a correspondence with the world of forms. (see Ernst Cassirer, The Problem of Knowledge.) The concepts and propositions that Euclid placed at the apex of his system were a prototype and pattern for what Plato called the process of synopsis in idea. What is grasped in such synopsis is not the peculiar, fortuitous, or unstable; it possesses universal necessary and eternal truth.

For Aristotle, the problem of the concept is transformed into the problem of teleology.

Read Moreideal / real

"Reality is what one does not perceive when one perceives it." Niklas Luhmann.

"My dialectical method is, in its foundations, not only different from the Hegelian, but exactly opposite to it. For Hegel, the process of thinking, which he even transforms into an independent subject, under the name of 'the idea', is the creator of the real world, and the real world is only the external appearance of the idea. With me, the reverse is true: the ideal is nothing but the material world reflected in the mind of man, and translated into forms of thought." Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 1,Preface to the Second Edition. (p.102)

Read Moreideology

The word "ideology" was originally coined by Count Destutt de Tracy, a French rationalist philosopher of the late eighteenth century to define a "science of ideas." For de Tracy, ideology formed "a part of zoology" (i.e. biology) The concept of ideology was developed in Marxian thought as a term through which to articulate the relation between the realm of culture and the realm of political economy. For Marx, the proper method for analyzing concepts is one which retraces the steps from the abstract concept back to its concrete origin.

"If in all ideology men and their relations appear upside-down as in a camera obscura, this phenomenon arises just as much from their historical life-processes as the inversion of objects on the retina does from their physical life-processes." Karl Marx, The German Ideology. (note the analogy between physiology in perception and social life in thought, both function as the concrete origins, if not as determinants.)

imaginary / symbolic

In the sense given to these terms by Jacques Lacan, the three essential orders of the psycho-analytic field are the Imaginary, the Symbolic, and the Real. The concept of the "imaginary" can be grasped through initially through Lacan's theme of the " mirror stage." Lacan proposed that the ego of the infant -- as a result of its biological prematurity -- is constituted on the basis of the image of the counterpart (specular ego). Following from this primordial experience, the Imaginary defines the basically narcissistic relations of the subject to his ego, the intersubjective relations of a counterpart -- an other who is me, a type of apprehension characterized by resemblance and homeomorphism -- a sort of coalescence of the signifier and signified. (from Laplanche and Pontalis) While Lacan's use of the term "Imaginary" is highly idiosyncratic, he insists that all imaginary behavior and relationships are fundamentally deceptive, and that the intersubjective realm of the symbolic must be separated out from the Imaginary in analytic treatment.

First page of Robert Fludd's Ars Memoriae 1619, showing the "eye of the imagination."

imagination

For Aristotle, in De anima, imagination is the intermediary between perception and thought. The perceptions brought in by the five senses are first treated or worked upon by the faculty of imagination, and it is the images so formed which become the material of the intellectual faculty. (Yates, p 32) Hence "the soul never thinks without a mental picture."

In the eighteenth century, "Fancy" or "imagination" applied to non-mnemonic processions of ideas. When images move in the mind's eye in the same temporal and spatial order as in the original sense-experience, we have "memory" This relation between imagination and memory follows Aristotle as well, for whom memory is a collection of mental images from sense impressions of things past. How do we distinguish between our own memories and our imagination? Modern researchers focus on "source memories" -- where and when we experienced something. Memories are generally accompanied by source memories, while imaginative thoughts do not have the same contextual components in time and space. But the loss of source memories or the imagined sense of location in time and space that can accompany dreams or vivid fantasies can make us unable to distinguish between memory and imagination.

Coleridge distinguished fancy from imagination, paralleling his distinctions between mechanical and organic. His theory of fancy singled out the the basic categories of the associative theory of invention: the elementary particles, or "fixities and definites" derived from sense, which he distinguished from the units of memory only because they move in a new temporal and spatial sequence determined by the law of association, and are subject to choice by a selective faculty -- the judgement of eighteenth-century critics. (Abrams, Mirror and the Lamp, p 168. Coleridge Bigraphia Literaria chapt. 13)

As opposed to this "aggregative" mechanical combinatory, Coleridge developed an organicist theory of the imagination, which is modifying and "coadunating." (a term from contemporary biology meaning to 'grow together as one.') He described the imagination as "vital" as "generating and producing a form of its own," whose rules "are the very powers of growth and production." For Coleridge, the imagination is "that synthetic and magical power, which reveals itself in the balance or reconciliation of opposite or discordant tendencies." This faculty "dissolves, diffuses, dissipates, in order to recreate; or where this process is rendered impossible, yet still at all events it struggles to idealize and unify. It is essentially vital , even as all objects (as objects) are essentially fixed and dead."

Thus the free play of the creative imagination makes up its own rules as it goes along and sets them according to the nature of the subject and the inspiration of the poet. "Imagination is no unskillful architect", for "it in a great measure, by its own force, by means of its associating power, after repeated attempts and transpositions, designs a regular and well-proportioned edifice." (Gerard, Essay on Genius, 1774) The "architectonic" impulse of the theoretical imagination renders phenomena intellectually manageable by presenting them in a "corrected fullness." (Sheldon Wolin).

The products of imagination Coleridge adduces most frequently are instances of the poet's power to animate and humanize nature by fusing his own life and passion with those objects of sense which, as objects, 'are essentially fixed and dead.' (Abrams Mirror and the Lamp, p 292) M. S. Abrams points out that almost all examples of this secondary or 're-creative' imagination would fall under the traditional headings of simile, metaphor, and (in the supreme instances) personnification.

"What distinguishes the worst of architects from the best of bees is this, that the architect raises his structure in imagination before he erects it in reality." Karl Marx, Grundrisse

"Imagination is an act by which we mentally simulate something that previously existed as a vague content of our sensation as sensuous, concrete form. If we then apply the same word to abstract thoughts, we thereby imply that these too are accompanied by mental images. " (Robert Vischer, "On the Optical Sense of Form," 1873) For Robert Vischer, the artist's imagination reunites the senses and the soul. "Both, in fact, were originally one, but in the course of its development the intellect placed itself in opposition to the senses, and only the artist succeeds in achieving their reunion." (p116)

For Kant, the imagination,(Einbildungskraft ) as a productive faculty of cognition, is very powerful in creating another nature, as it were, out of the material that actual nature gives it. Imagination is the faculty of mind which enables us to combine representations. (see Critique of Judgement sect. 49. see also intuition.) Using the etymology of Bild, one can say that the imagination synthesizes the manifold of intuition into a tableau-like unity, and Kant assigns an essential role to the imagination in synthesizing the disparate mental realms of sensibility, understanding, and reason. (See Gasché , p 217) Yet for Kant, the imagination is unequal to the ideas of Reason. The experience of the sublime, either in the form of magnitude or power, causes a painful awareness of the inadequacy of the imagination, but for a rational being there is a pleasure in this awareness, a harmony in this contrast. (see sect. 27) Kant uses the German word das Erhabene, which can mean raised, embossed, or lofty.)

Freud, too, stressed the inadequacies of the imagination, which he described as "the over-accentuation of psychical reality in comparison with material reality." (Das Unheimliche , p.244) In his descriptions of the uncanny (unheimlich ), Freud observed a weakening of the value of signs, in which the symbol ceases to be a symbol and "takes over the full functions of the thing it symbolizes." For Freud, this assertion of "the omnipotence of thought" requires the invalidation of the arbitrariness of signs and the autonomy of reality as well, placing them both under the sway of fantasies expressing infantile desires or fears. (Kristeva, p. 186)

For Gilles Deleuze, imagination is a circuit between the actual and the virtual. Imagination means how we see and how we learn to see, how we suppose the world works, how we suppose that it matters, and what we feel we have at stake in it.

In a very different context, Arjun Appadurai describes the joint effects of media and migration on the work of the imagination as a constitutive feature of modern subjectivity. This is a collective imagination, not the faculty of a gifted individual, and it forms the basis for a "community of sentiment." (what anthropologists call a sodality) Here Appadurai follows Benedict Anderson's analysis of the modern nation as "an imagined political community." For Anderson, "it is imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion." (Imagined Communities, p. 6) Appadurai describes media and migration as resources for experiments with self-making in all sorts of societies, for all sorts of persons. The mobile and unforeseeable relationship between mass-mediated events and migratory audiences defines the core of the link between globalization and the modern. In this context, the work of the imagination is neither purely emancipatory nor entirely disciplined, but is a space of contestation in which individuals and groups seek to annex the global into their own practices of the modern. (p.4)

(see also public / private)

For Appadurai, "The imagination is today a staging ground for action, and not only for escape." (an expression which should gratify those whose slogan in 1968 was "l'imagination au pouvoir." ) He describes "culturalism" as a mobilization of identities consciously in the making and as the most general form of the work of the imagination.

Kant Copernicus

Introducing the revised version fo the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant, in a now proverbial analogy, likened the procedure of his philosophy to that of Copernican astronomy: both propose a change in the position of the observer in order to explain apparently errant or contradictory phenomena.

Read Moremechanism/vitalism

The prestige of mechanistic physics after Newton led to an extended confrontation between the norms of physics and other areas of science such as biology and psychology. Newton's Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophystood as a classical prototype, or canon, by which to judge all subsequent science. Newton's great achievement was to have produced a mathematical theory of nature that provided general solutions based on a rational system of deduction and mathematical inference, coupled with experiment and critical observation. Newtonian mechanics established "universal laws" that explained the movements of the planets, the tides, and whose predictive powers were given an overwhelming demonstration with the appearance of Halley's comet, just as predicted, in 1758, long after both Halley and Newton were dead. Even today, the exploration of space is a straightforward application of classical gravitational mechanics.

Read Moremorphospace

The theory of what Stephen Jay Gould has called morphospace is that space of possible morphologies for species organized according to certain principles. Proponents of robust morphogentic processes, such as Stuart Kaufman or Richard Goodwin, see these processes as having large basins of attraction in morphospace.

Read Morenarrative

Why is narration so universal? What psychological or social functions do stories serve? Why is our need for stories never satisfied? And why do we need the "same" story over and over again? (J. Hillis Miller, in Critical Terms for Literary Study.)

In the Poetics, Aristotle claims that plot is the most important feature of a narrative. A good story has a beginning, middle, and end, making a shapely whole with no extraneous elements. Aristotle also addressed the social and psychological role of narration. He described tragic drama as the purging or catharsis of the undesirable emotions of pity and fear by first arousing them and then clearing them away.

A large contemporary literature has explored diverse theories of narrative, including Russian formalist theories (Propp, Sklovskij, Eichenbaum); Bakhtinian, or dialogical theories (Mikhail Bakhtin); New Critical theories (R.P. Blackmur); Chicago school, or neo-Aristotelian , theories (R.S. Crane, Wayne Booth); psychoanalytic theories (Freud, Kenneth Burke, Lacan, N. Abraham); hermeneutic and phenomenological theories (R. Ingarden, P. Ricoeur, Georges Poulet); structuralist, semiotic, and tropological theories (C. Levi-Strauss, Roland Barthes, Tzvetan Todorov, A.J. Greimas, Gérard Genette, Hayden White); Marxist and sociological theories (Georg Lukacs, Frederic Jameson); reader-response theories (Wolfgang Iser, Hans Robert Jauss); and poststructuralist and deconstructionist theories (Jacques Derrida, Paul de Man) .